We’d already run 18 euphoric miles through the woods, along the June shores of Lake Superior, but as we crossed mile 19, Brandon and I were no longer talking.

I could hear his breath coming down his nose in sharp cuts. I was counting half miles, then quarter miles, then tenths of miles, adding up increments left until we’d cross the finish in downtown Duluth, Minnesota. When we left the tree line, Superior disappeared. I could still hear its waves lapping listlessly underneath the clang of spectators’ cowbells, but now we were plodding down I-35 southbound, looking up at a 250-foot stretch of asphalt climbing before us—the only hill on the course of Grandma’s Marathon, the infamous Lemon Drop Hill.

We climbed with our heads down, Brandon taking on a jerking, off-center gait. He was leaning into his right leg and breathing intensely. He said something guttural and profane and pulled up. “My quad,” he said, limping over to a concrete barrier.

We started talking again, this time arguing. I wanted to stay with him. We’d been together since we first started training for this race 16 weeks earlier. Together in some way since I was in sixth grade and he joined my youth hockey team. It didn’t seem worth it to cross the finish without him. But Brandon nearly shoved me off when I hugged him goodbye and started out for the final 4.2 miles.

For the first time, I was alone.

RUN LIKE THE LAKE RUNS

Until I was 25, I had never run a mile without stopping.

I didn’t have a runner’s build. I was stocky, built like a Sicilian plumber. In school, I walked whole laps, averaging 11-12 minutes for a full mile. My junior year of high school, I resolved to run an uncompromised mile, but my gym teacher accidentally recorded my time after only my third lap. He read out my results: 8:37. I stopped right there and never thought about running a time trial again.

That changed in 2014 when my brother-in-law, then a park ranger at Glacier National Park in Montana, invited me out to visit the park. It wouldn’t be the kind of hiking we’d done in Massachusetts. Glacier is over 1 million acres of alpine woods. Elevation starts at 3,150 feet. The air there is empty. Breathing can feel like climbing a silk rope.

I started running 1-mile laps around my block in South Minneapolis. Three left turns and home, three days a week. Gradually, the runs started getting longer as I ventured further, out to the shores of Lake of the Isles, a tomahawk-shaped body that sits in the lowlands between Minneapolis’ most comely neighborhoods. Reaching its shores felt like a “Rocky” moment. If I made it to the southwestern bank—across from the dredged-up island where the dead aspens stick out like shards of animal bone—and back, it amounted to a 5K. So, I started running 5Ks.

Running was somatic. It was an effort to teach my body, a ramshackle machine, how to live better than its design. But when I was near water, I didn’t think about my body. Running was spiritual. The heat reflecting off the concrete gave way. My eyes expanded to take in the wide-open spaces. Lakes, rivers, and canals are popular runner locales, mostly because they offer flat terrain, but there’s something about water that gives people life. Maybe it’s caveman brain, but the first stride along the shore always gave me relief. Suddenly, the city was a pulsating plane of life, dappled with lily pads, and the earth below me was kind.

That year, I cheered my downstairs neighbor as she ran the Twin Cities Marathon. I waited for her along Minnehaha Creek, watching a parade of forms go before me. Some of the men, lean and sinewy, looked like how I imagined marathoners. But other men looked just like me.

After two months of running Minneapolis lakes, I was ready for mountains. Montana was confirmation that the training had worked. I clambered up the spine of the Rockies, paced by marmots and mountain goats. I kept my breath for 8 miles and 1,600 feet to Grinnell Glacier, and at the end of the trail, I took off my socks and tiptoed through the cloudy glacial runoff.

HIGHWAY 61 ALL THE WAY

The morning of Grandma’s Marathon, I was shivering next to Brandon, my lifelong Masshole friend, in Two Harbors, Minnesota, 26.2 miles north of the finish line in Duluth’s Canal Park.

I snuck away to piss in a row of juniper shrubs with 50 other marathoners also suffering from panic bladder, and I returned to find Brandon in our 9-minute-mile pace group, about 500 feet from the starting line. The crowd of almost 10,000 runners was surging with adrenaline and pre-workout jitters. Brandon was gabbing excitedly with a pace-mate about Nikes. A guy behind us—a 7-foot adonis with a hydration backpack—chimed in to talk about his neon supershoes. Brandon and I peeled off our warmup layers to reveal custom running singlets we had designed for the race. They were in the style of our youth hockey team’s jerseys, complete with our names across the shoulders and the Hawks logo on our chests.

It was Brandon’s second-ever visit to Minnesota, and his first time enjoying one of the state’s signature 50-degree July mornings. The sun was climbing out of the fir trees, and the first rays caressed our now-bare shoulders. After I moved to Minnesota, I would routinely return to the East Coast for a wedding or a holiday, and I’d meet up with Brandon and our friends, and we’d all get drunk, and they’d ask, “What the fuck is there to do in Minnesota?” It was scenes like these I pulled together to silence their cynicism.

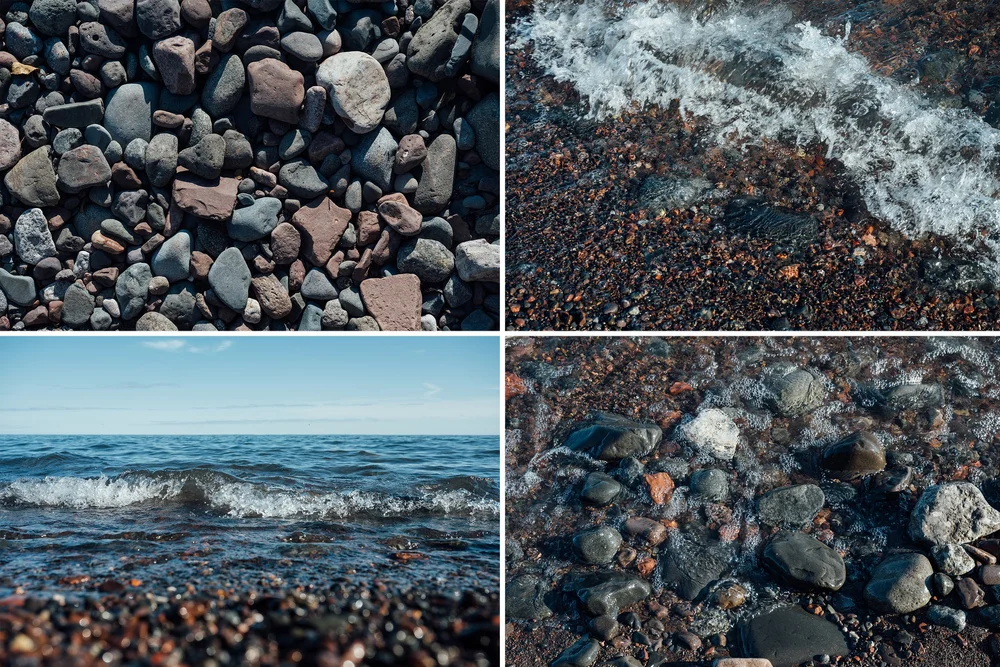

I told them about the lakes I’d been running, about how Minneapolis has clear, verdant spaces where you can watch muskrats swim in all directions. But mostly I talked about the North Woods, the land two hours north of the Twin Cities where the Sawtooth Mountains give way to the copper, nickel, and iron mines that bore through the cradle of Lake Superior’s western shore. It is a spellbinding landscape, dappled with aspens and birches, where sandstone cliffs stand high over the waves and candy-colored agates spontaneously appear in the sand.

In 2013, Business Insider called Northern Minnesota, “the Mongolia of America.” It was an unkind analogy, as the Miami-based writer gawked at the ore mines and taconite stockpiles of Hibbing and Duluth like they were some kind of industrial Gomorrah. It’s the kind of miss-the-mark parachute journalism that has come to rankle native Minnesotans, who look at the Lake Superior Basin the same way Bob Dylan did.

“The earth there is unusual, filled with ore,” the Minnesota-born singer told Playboy in 1996. “There is a magnetic attraction there. Maybe thousands and thousands of years ago, some planet bumped into the land there.”

It is a spellbinding landscape, dappled with aspens and birches, where sandstone cliffs stand high over the waves and candy-colored agates spontaneously appear in the sand.

Grandma’s traces Highway 61, the legendary coastal highway that served as the muse for Dylan’s 1965 album “Highway 61 Revisited.” It’s the only road up to Grand Marais, an artist community on the North Shore where I once got caught in leaden rain. It’s the road to Gooseberry Falls and Split Rock Lighthouse, sentinels of Superior’s craggy North Shore. Historically, it was a proving ground for men who strained their flesh pulling metal from the earth. I’d driven the way a dozen times, and now here I was, taking it by foot with a friend I’d once had to convince of its beauty.

The starting pistol went off, cutting through the metal air, followed by the sound of 10,000 synching Garmins. In the echo, the throng began an anxious creep toward the starting line.

PARALLEL PATHS CONVERGE

Brandon and I met in the cold. It was a frigid locker room at Hobomock Arena in Pembroke, Massachusetts, in 2000. Brandon had just joined my peewee hockey team, the Whitman-Hanson-Kingston Hawks, after a few seasons in a higher-tier league.

He was a slick-looking forward with lots of speed. I was an undersized, mouthy goalie whose dad coached the team. Brandon was immediately our best player. Coaches would lean on Brandon late in games when we were tied or trailing, and he would routinely deliver.

Brandon was a graceful, powerful skater. He wasn’t afraid of what his body could do. It made me feel inadequate, and angry. Our positions made us competitors, but my insecurity made us rivals. I treated every practice drill like a championship matchup. Making a save on him shot adrenaline through my chest. He was better than everyone else, and he knew it, but what I never told him was that I wanted to be just as good as he was.

We bristled against each other and jaw-jacked for years. I got better, and he stayed good. When we were 14, we enrolled at the same private high school, playing freshman hockey together. We’d end every practice with one-on-one breakaways. Years later, my college team played against his in Tampa. We were benched for the game, so we sat in the stands together and drank Bacardi Dragonberry and Sprite.

In 2014, I moved to Minneapolis. Around the time I started running, so did Brandon.

I watched him complete his first marathon from a half-country away. Through the occasional Instagram post, I saw my once-rival completely surpass me, just as I was beginning my own journey with running. When I finally joined Strava, a social app for runners to share workouts, it felt like sixth grade again. I’d post a trio of 10-minute miles, and he’d be setting personal bests at double-digit distances.

In the summer of 2022, Brandon was looking for a race, and he’d heard good things about Grandma’s from other runners. The concept of a breezy run along North America’s largest lake intrigued him, but it was also an opportunity to kindle a new era of our friendship. He texted me, asking if I’d join him.

I took a beat. I turned the idea in my head. That morning, I’d run three soft miles around Powderhorn Lake, an absent plod. Could my body do more? I answered him before I really reconciled what I was committing to.

“If I was ever gonna do one, it’d be Grandma’s,” I replied. “And it’d be with you.”

SIXTEEN WEEKS IN SYNC

Brandon recommended we work the same program, a 16-week slog he’d found in Runner’s World. The program would get us to the finish line in 4 hours, right around a 9:08 mile pace.

These numbers seemed hypothetical to me as I started out on my first training run in March, an icy, 36-degree, 4-mile outing that came in just under marathon pace. The air was still with cold, and all I could think about was violence. I slipped across the sidewalks, terrified that a van would skid through a stop sign just as I crossed. When I made it back home, I had a text waiting from Brandon. He’d gotten a driving rain, but he’d managed to finish, too.

My runs morphed into Brandon’s runs. I could see his Strava maps like my own, the patterns overlapping despite the distance between us … Our bodies were synchronizing without ever being in the same place.

We shared our suffering four days a week, the miles becoming our mutual antagonist. Commiserating about runs turned into drawn-out conversations about our plans for our lives. He told me about changing jobs after our first long-run Sunday. We groaned about hill workouts and mused about the shit our kids did in school. We were shopping for matching shoes when he slyly told me that his wife was pregnant with another daughter. Soon after, I told him I was moving back to New England just in time to travel with him back to Minnesota for our race.

As our program advanced and the miles piled up, Grandma’s became more real. I ran to edges of Minneapolis I’d never seen before, pushing myself through railyards and underneath highways. I tiptoed through the Mississippi River when it swelled into the streets. My legs grew thick.

My runs morphed into Brandon’s runs. I could see his Strava maps like my own, the patterns overlapping despite the distance between us. I learned the patterns of his town, the way the bike trail in his town curved. I could tell when he was visiting his in-laws by the shape of his course. Our bodies were synchronizing without ever being in the same place.

My move came during week 14, the most difficult week of training. That week, I was sentenced to a 21-mile Sunday slog, smack in the middle of my cross-country drive. I woke up in an Aloft hotel in rainy South Bend, Indiana, and found the St. Joseph River. It carried me for 6 miles through the woods before I lost it for the last 15. It was a torturous morning. Around mile 18, I ran up on the St. Joseph again, and there I saw a fire rescue team pulling a car out of the waterway. I envied the driver, and the power of the current.

When I got back to my hotel, I texted Brandon: ”That was tough, but I think if I had someone with me, I could’ve done the last 5.2.”

ALONE ACROSS THE LANDSCAPE

True to training, the first 9 miles of the marathon were a glorious laze. The course unspooled before us, easy and inviting.

Brandon and I were vibrating with joy. Runners ran by with speakers hitched to their shorts, and we sang along to “Eye of the Tiger.” We ate pancakes that Two Harbors residents handed out at the ends of their driveways. We talked to a man in his late 60s who was running his 30th Grandma’s. He told me about running 100-mile relays and that he’d be shuffling through his last marathon, lord willing, when he was 80 years old.

We were underneath the pines, falling into the rhythm of the planet. This is what we’d taught our legs to do, and the training reverberated through the environment. Our sneakers thrummed against the pavement underneath the trill of unseen birds, each footfall a note in a paradiddle we played with our bodies, the national anthem of America’s Mongolia. When the road emerged and the shoreline opened up, crowds appeared, drinking Bloody Marys and holding signs. They felt like family, even though I couldn’t see their faces in my blurring bliss.

“Let’s go Hawks!” some chanted as Brandon and I passed in our matching attire.

At some point, the running turned inward. The sun ascended and the tree line thinned in a cruel gradient. We ran through water stations ravenously, grabbing for cups and sponges. I could sense Brandon to my side—always my left—but our voices disappeared. My pulse resounded like timpani playing inside my head. Between beats, I heard Brandon struggling. All I could think about was sixth grade. There was so much I wanted to tell Brandon, emotions I’d been holding since we were prepubescent rivals.

At mile 19, we crossed into Lester Park. There, Duluthians gathered to tailgate and cheer on runners. I tried to take their energy inside me. When a fratty group offered me a paper cup of Michelob Golden Light, I said fuck it and threw the contents in my face. Brandon was foraging for anything to fuel him onward. He ate pickles and watermelon in succession. A packet of maple syrup. But he was losing steam. When we got to Lemon Drop Hill, despair set in.

That’s when I told him. Through a grimace, I told him about how I’d wanted to be here today because I’d been trying to convince myself our whole friendship that I was as good as him. That I belonged in the same locker room. He’d set the standard not only on the ice, but in school, in fatherhood. In life. But these 16 weeks had taught me that we had never really been in competition. We’d been pushing each other, yes, but for something mutual. We recognized ourselves in each other. We’d never said it before, but I wanted to now, if it meant we could finish this race together.

“I wish you hadn’t told me that,” he said. In a moment, I knew why.

When Brandon’s quad gave out, I felt his groan cut through me like cold steel. His body was starving for glycogen. I thought it was over. We’d be carted back to Duluth, defeated. Sixteen weeks of shared anguish squandered because of a stubborn thigh, a body giving way. I tried to follow Brandon into the med tent, but he wouldn’t let me. He let me stop long enough for a second piss. Then he told me to meet him at the finish line.

I hugged him goodbye, and sprang out of the embrace without looking back. Now on my own, I accelerated irresponsibly down the highway. There was no charm left on my route, and what was once boreal forests and placid shores was now shoulder-to-shoulder pavement. Mile-long outcroppings were replaced by regional gas stations. I couldn’t muster a word to my fellow runners. I ran with my head down, counting steps.

I didn’t think about anything except water. I probed my body with my mind, finding all its vulnerabilities. The tightness in my hamstring. The blisters on my heel. It was damning me, again.

When Brandon’s quad gave out, I felt his groan cut through me like cold steel. His body was starving for glycogen. I thought it was over. We’d be carted back to Duluth, defeated.

Around mile 24, the 7-foot bodybuilder came up on me, patting me on the shoulder. “I passed your buddy a while back,” he said, “you’re way ahead.” I puzzled over his words. I don’t think I gave him a reply. Brandon and I had been together every inch of the marathon until Lemon Drop Hill, where he dropped out. Was he running again, somewhere in the thinning horde behind me? I came down through downtown Duluth, past a theater where people shouted “Let’s go Hawks!” from the sidewalk. I didn’t even bother looking to see if there was someone else they were cheering for.

The last 2 miles were a gasping ordeal. I watched other runners wobbling like their knees were made of ballistic gelatin. I receded totally inward, even as I turned the last corner, past the tankers in the harbor, and into the final stretch. At this point, I couldn’t even look at the lake. Just my watch and shoes.

Down the home stretch, there were runners clinging to the guard rails. One man fell on his face beneath a pedestrian bridge in the final turn. In the last quarter mile, I saw a camera peeking out from a balloon arch above me. I raised the Hawks logo on my singlet as a signal to my friend, somewhere in the North Woods behind me, hoping he’d be soon behind me. I finished alone, and finishing felt like nothing more than stopping.

When I called my wife, she asked me how I felt. I didn’t know what to say. The only thing I could feel was relief—relief that the run was over, that my shoes were off, that I’d come to a rest. The first time I felt any sense of pride or accomplishment was when she mentioned that Brandon was almost finished. She’d been tracking our bibs from home, and she saw him coming in, only 12 minutes after me.

I pushed myself up from the asphalt, the heat blanket falling from my shoulders. I searched for a matching jersey in the sea of exhausted runners around me, my brain finally comprehending the feat my body had completed. My ankles felt like stone, but I wanted to leap to see above their heads.

When I thought my legs would finally buckle, I found Brandon, smiling with big teeth from across the parking lot. We were abominations, masses of sweat and cinnabar. Our singlets were twisted out of shape, the Hawks logo nearly unrecognizable. But it was a triumph. We’d made it out.

We both had.